ICT4LT

Module 1.3

ICT4LT

Module 1.3 ICT4LT

Module 1.3

ICT4LT

Module 1.3This module aims to demonstrate how the word-processor and presentation software can be used effectively to support language learning. Sections 1-4 offer practical advice and examples. Section 5 focuses on different ways of entering foreign characters into a word-processor. In Section 6 there is a brief discussion of the pros and cons of grammar and style checkers and the use of a thesaurus with advanced learners, and there are links to sites offering further ideas. Section 7 is devoted to Using PowerPoint, and Section 8 describes how to enhance Word and PowerPoint documents with pictures and sound.

This Web page is designed to be read from the printed page. Use File / Print in your browser to produce a printed copy. After you have digested the contents of the printed copy, come back to the onscreen version to follow up the hyperlinks.

Graham Davies, Editor-in-Chief, ICT4LT Website.

Heather Rendall, Freelance Educational Consultant, UK.

The commonest ICT tool for creating and manipulating text is the word-processor. A word-processor is an extremely useful piece of software, enabling teachers to produce professional-looking documents that can be printed and used as handouts or worksheets for learners. The worksheets can also become electronic worksheets (see Section 3 and Section 4) and they can be enhanced with pictures and sound and exported into other applications such as PowerPoint: see Section 8.

These are the essential skills that you need to acquire:

You can do many more things with a word-processor: see the section on Microsoft Word in our ICT_Can_Do_Lists document.

The advantages that word-processing skills bring to the teacher of Modern Foreign Languages are enormous. Teachers spend hours making materials to use with their classes. A word-processor speeds up the process and enhances the quality of production that can be achieved. Add to this the instant availability of your materials, not just for yourself but any other member of staff, and the fact that you can differentiate the material easily to suit new classes, then suddenly you are looking at a way to save time and effort and to gain better and more adaptable resources. Furthermore, any materials you create with a word-processor can be copied into email messages, discussion lists, blogs and wikis and made available to a wider audience via the Internet: see Section 12, Module 1.5, headed Discussion lists, blogs, wikis, social networking, and Section 14, Module 1.5, headed Computer Medicated Communication (CMC).

See Section 6.3 for links to additional ideas and resources. See especially:

MFL Resources: This website contains a number of downloadable resources created with Microsoft Word: http://www.mflresources.org.uk/

MFL Sunderland: Lots of useful downloadable resources and information here and links to other useful sites. Created and maintained by Clare Seccombe.

Teacher's Pet: A website created by Chris Lacey, which offers a free text tool, a Microsoft Word template which contains sets of macros that can make simple but very useful changes to texts in order to create word-processing exercises, e.g. removing spaces, removing vowels, word-jumbling, sentence jumbling, breaking sentences in half, etc. See the Using Teacher's Pet tutorial by Joe Dale at the CILT website.

Many of the above exercises, especially those designed to be used as electronic worksheets, can also be created with the aid of authoring programs: see Module 2.5, Introduction to CALL authoring programs. CALL authoring programs often consist of a set of templates that offer a far less labour-intensive approach to creating exercises.

Exercise books, like all paper and pen activities, have one serious disadvantage: they are linear. New material can only be added after the last piece of work, even though it may have greater relevance to a text or exercise some pages back. To some extent minor errors can be corrected - messily - by erasing with correction fluid and over-writing, but inserting a whole phrase or sentence, even if there is space, makes the text not only untidy but difficult to read. If correction, insertion and deletion are employed on a constant basis, the end product becomes illegible and therefore unacceptable.

A word-processor, by contrast, allows all these and still produces perfect copy. Mistakes can be erased without a hint of correction; new words or phrases can be inserted without harming the original text; texts from various topics can be merged to produce longer, more involved dialogues or situations; simple sentences can be enhanced by more complex grammar; tenses can be changed.

In other words, written production via a word-processor can parallel language development: as new ideas and vocabulary are added to the store of knowledge, so can an original, simple text be expanded, altered and stylistically enhanced. And in doing so the student is given an implicit demonstration that language grows from the inside out - not in a linear, topic-based fashion.

As well as helping students develop writing skills, the word-processor can be an invaluable aid to the teacher for marking and giving feedback. We deal with this topic in Section 3, Module 4.1, headed Using a word-processor for marking and giving feedback.

Access to a local area network (LAN) is recommended so that a whole class can be engaged simultaneously. Next best option would be access to a computer cluster (3-4 computers) with students being given a time limit for their writing and access being rotated round the class. The least preferred option would be access to a single computer in the classroom; even as part of a carousel, the time required for all students to gain sufficient access would be too long.

How often would you have to gain access to the computer network room for writing with a word-processor to be a valid exercise?

Students could build up from a series of original texts, each of which combines sets of related topics, e.g. one text could be titled "Me and my family" and cover such topics as the home, pets, siblings, personal descriptions, routine activities, leisure activities, chores, pocket money, holidays.

What other topics usually studied by initial learners could be grouped together to make valid texts?

Any productive task is best set towards the end of any module or topic, on the grounds that receptivity for new material comes first, productivity later. Asking students to produce a piece of writing that includes a large proportion of new material, vocabulary and structures, is a useful measure of how much a student has gained from the latest work.

How would you ensure that students don't just tack new material on the end?

Each student will need to save their work twice. The first time will be the uncorrected effort of the student; this is what gives the teacher the measure of the student's competence. The text is printed out and corrections and/or suggestions are made by the teacher. The student returns to the computer and uses the teacher's comments to improve the text. Once this has been done to the teacher's satisfaction, then the corrected text is saved under a different file name. This method will ensure that:

a. corrections and suggestions are acted upon,

and

b. the next time the student wishes to add or alter the text, they will be doing

so from an accurate base.

What kind of file naming system would suit here:

a. If each student had their own area to save

to?

or

b. If each class had an area to save to?

Over a period of learning, students at school level tend to cover similar topics whichever course book they use and whichever exams they are being prepared for. Students working on advanced level material cover topics totally different in both style and content. Students at university level beginning a new language may well cover both types of topic. Whatever phase you work in, draw up a long-term plan of writing tasks, in which you relate as many topics as possible.

Take any one of these tasks and plan the likely development of language.

For example, in writing about "Me and my family" simple adjectives of size and colour may well be learnt early on, but adjectives describing people's personal characteristics may not be learnt until some time later - maybe as long as two years later. Relative clauses may not be learnt until later still but would enhance statements made years previously.

This section focuses on practical examples of electronic worksheets containing simple reinforcement and recognitions exercises.

Contents of Section 3

The first step in vocabulary learning is recognition. Wordsnake exercises appear in many elementary textbooks as a preliminary exercise in recognition. Students have to break down the "snake" into its component words. The reasoning behind this is sound: if you are able to pick out words, you must have a graphic image of each one in the brain against which you are checking the shape, the spelling, the whole image of the word, or whatever, of the chains of letters in the "snake".

It sounds almost too simple to be credible; but try it out with learners who have just been introduced to new vocabulary. Initial learners who have yet to develop a feel for the target language orthography, will have little difficulty in spotting well known words, some difficulty in deciding the exact length of words only half known and will miss completely other combinations of letters which you would have believed were instantly recognisable as having been part of lessons over the previous few weeks!

Why use the computer? Because it allows students to experiment with shapes of words and spellings. Using the cursor keys and the space bar they can pan along the line of letters, stopping when they believe they have arrived at the end of a recognisable word and space it out from the line. If, after reflection, a mistake seems to have been made then it is easy enough to back-space to the original sequence of letters.

A quick way of creating a Wordsnake exercise:

You can get rid of line breaks thus:

You can strip out any punctuation marks in a similar way.

Here are some examples of Wordsnakes:

glaceseauoeufpâtécrêpemielcitronthéchocolatframboisevanillefritesvin

eiswassereierpastetepfannkuchenhonigzitroneteeschokoladehimbeer

You only have to try in a language not familiar to you to see the real impact of this exercise on a learner.

kramainggilmadyangokognokobiasaapakowéarepmangansegalankaspésaiki

(see Crystal 1987: 40)

Or in a language that is familiar but not well known:

Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch

This is a real place name. Can you find

out where it is, what it means and how to break it up? Search the Web! If you

can't find the answer, just click here: Cheat

Phrases can also be treated in this way, especially useful in a language such as French, which has a high incidence of elision. In the following example not only spaces but apostrophes have to be inserted as well:

Ilssappellentilyenacinqcayestjenaipasdamieillavuquestcequecestjenelaipas

The Teacher's Pet text tool by Chris Lacey, can also be used to generate Wordsnake exercises in Microsoft Word.

Once chains of letters have been completed, the exercise can develop in various ways. Here is one example:

Using the space bar, reveal the words in this chain. Then cut and paste them into the correct gender boxes beneath. Finally write six sentences with one of the words in each sentence to be used in the Lost Property Office.

Use J'ai perdu mon / ma / mes...

Pelliculechapeaumanteauécouteurslunettesbraceletparapluiesacappareil

|

le

|

la |

Target language testing needs students to be able to make many different connections between items of vocabulary. The reason is quite simple: when using the target language in the question, the examiner has to avoid using the same word as in the text… otherwise it becomes an easy task of direct matching. Examiners get round this by using among others ploys: synonyms, circumlocutions, opposites and negatives, double negatives and invisible negatives and collectives.

Note: Only abbreviated examples are given: actual exercises would have more content.

3.2.1 Example: negatives and invisible negatives

i. Students have to cut and paste a series of statements from a table to one of two columns - positive statements and negative statements:

| I don't care | Worthless! |

-

|

I don't dislike it |

| I'm quite happy with that | It's brill |

-

|

I am ecstatic |

| It's not bad | Fabulous! |

Rubbish!

|

I can't put up with it |

| Hardly worth it | I'm fed up |

-

|

It's worthwhile! |

| :-) |

:-(

|

ii. Students cut items from a box and paste them under the correct shop heading:

| Rindfleisch | Seife | Mehl | Socken | Zucker | Anzug | Pille | Pastillen |

| Watte | Keks | Schnitzel | Rezept | Weißwurst | Essig | Kotelett | Eis |

| Leber | Handschuhe | Gemüse | Kleid | Truthahn | Pflaster |

-

|

-

|

|

Apotheke

|

Metzgerei | Konditorei | Kaufhaus | Lebensmittelgeschäft |

iii. Students cut and paste weather statements into columns headed by Beau temps and Mauvais temps:

| il pleuvait | il n'avait pas de nuages | il faisait une chaleur | il grèle |

-

|

| il faisait extrément froid | le soleil brillait de temps en temps | ciel couvert |

-

|

-

|

| il pleuvait à verse | agréable | orageux | risque de pluie | éclair |

| verglas | chutes de neige |

-

|

vent fort | éclaircie |

|

Beau temps

|

Mauvais temps |

Create similar exercises to deal with:

i. synonyms

ii. opposites

iii. idiomatic expressions.

Work out a way in which to include such exercises in a topic that you already deliver. This could be as a class exercise, an independent / home exercise, part of a carousel or differentiation material (either for the top or bottom).

This section focuses on practical examples of electronic worksheets to assist language learners to develop concepts of basic grammar, e.g. verb forms, word order, use of adverbs and adjectives, and inflexions.

Anyone learning a new, unrelated language has to create a certain amount of new cognitive behaviours, e.g. the English speaker has no concept of gender other than that applied to the actual sex of humans or animals (with the faint exception of ships and motor cars, which are referred to as "she"). A French speaker, despite having a practised cognitive route for gender, has to create new routes to cope with German case endings, which are unknown in French. A German moving to English has to build ways of dealing with the multiple forms of each person in every verb tense. A Finn or a Hungarian has to face the new notion of free-standing prepositions.

When any human has a new experience, the brain first of all tries to make connections with information already stored; if this proves impossible because nothing is related, then what are called "activity-dependent brain changes" take place. Fresh neural pathways have to be set down in the brain, honed and polished by practice into existence and then re-visited as often as possible if the information stored is not to be lost. See Rendall (2003) and Rendall (2006).

Once upon a time much of this was done by rote learning; essential information was drilled into students on a regular basis, whether they understood its significance or not. Given the initial prompt, the well-trained brain would start on an inexorable outpouring of facts, figures, computations, verse, mnemonics etc. Foreign language teaching was not exempt and many a ex-British school student, who still in adult life is unable to communicate satisfactorily in French, can, when asked, repeat the formulas:

In the era of communicative language learning, such rituals all but vanished - and some teachers mourned their passing, feeling that at least they offered a first step on the way to knowledge and competence, even if the following steps were never accomplished.

It is possible to resurrect rote learning but not as the sterile chant of all those years ago but as the verbal pathway to an active procedure that the brain has to develop in order to cope with new grammatical concepts in foreign language learning. What makes this rote learning different is that it is both verbal and active - on the word-processor.

What cannot be done on paper, can be done on screen. As students listen, they can act. Told to remove an infinitive ending and add a personal ending, they can do this using the facilities of the word-processor. Told that pronouns come in front of the verb, students can delete the now superfluous noun and drag-and-drop the said pronoun in the proper place. Asked to create verb tables for irregular verbs, they can cut and paste from a list into ready-made boxes titled: infinitive, present, preterite, past participle.

The brain now has much more to absorb than rote learning ever offered: the sound and meaning of the words are the same but to this is added, the sequence of steps taken, the movement of individual words, the changes to be made. All these become part and parcel of the memory. Now when the prompt is given, it will not just be a verbal response but an action that produces a desired affect.

The "verbal pathway" could come from the teacher or a tape or written instructions on screen or paper. Which method would suit what level of student best?

Start with a clear screen.

Ask the students to:

| i. Type in the verb regarder (or any other useful regular -er verb) | - |

| ii. Copy the verb into memory: double click on the verb to highlight it and then press CTRL + C | - |

| iii. Press ENTER twice | - |

| iv. Enter 1st person pronoun plus a space | je |

| v. Press CTRL + V (copies verb to screen) | je regarder |

| vi. Remove the -er | je regard |

| vii. Add -e | je regarde |

| viii. Press ENTER | - |

| i. Enter 2nd person pronoun plus a space | tu |

| ii. Press CTRL + V (copies verb to screen) | tu regarder |

| iii. Remove the -er | tu regard |

| iv. Add -es | tu regardes |

| v. Press ENTER | - |

| i. Enter 3rd person pronoun plus a space | il |

| ii. Press CTRL + V (copies verb to screen) | il regarder |

| iii. Remove the -er | il regard |

| iv. Add -e | il regarde |

| v. Press ENTER | - |

Continue until all six persons, singular and plural, are completed.

Ask students to enter another -er infinitive and repeat the whole exercise again. Then show a list of familiar regular -er verbs on an interactive whiteboard or wall screen using a standard data projector and ask students to complete any three of them. For further information on using interactive whiteboards see Section 7 (below).

A verbal exercise could follow to see how well they are progressing; Can they already produce the nous form of jouer without looking at the screen? Similarly, the tu form of dessiner, the ils form of patiner.

If more practice is needed, ask for another three verbs to be completed. Talk them through the first one again, step by step.

If you wish to visually emphasise the singular/plural aspect, you can prepare the file in advance. Create a workspace with a table consisting of two columns and eight rows, so that the infinitive can be entered into top left-hand box, followed by the singular forms. The plural forms are entered in the right-hand column.

|

regarder

|

|

|

Singular

|

Plural

|

| je regarde | nous regardons |

| tu regardes | vous regardez |

| on regarde | - |

| il regarde | ils regardent |

| elle regarde | elles regardent |

At what stage would you include meaning(s) into this work?

What other grammar points could be treated this way?

Word order in German

Prepare a file with familiar sentences using Subject Verb Time Phrase (S V TP), e.g.

Mein Vater fährt jeden Tag mit dem Auto in

die Stadt.

Ich spiele samstags Fußball mit meinen Freunden im Park.

Viele Wildblumen sterben jedes Jahr auf dem Lande aus.

Explain that German frequently mentions time phrases (when? phrases) first but that the main verb must still remain as second idea. So two things have to be swapped: Subject and Time Phrase.

Ask students to:

i. Highlight jeden Tag by holding down

the left mouse key and dragging the cursor from the beginning to the end of

the two words:

Mein Vater fährt jeden

Tag mit dem Auto in die Stadt.

ii. Release the left mouse key.

iii. Point the cursor back into any part of the highlighted jeden Tag and hold down the left mouse key.

iv. Drag jeden

Tag to the front of the sentence:

jeden Tag Mein Vater fährt mit dem Auto in die Stadt.

v. Repeat the highlight and drag-and-drop procedure

with Mein Vater:

jeden Tag fährt Mein Vater mit dem

Auto in die Stadt.

vi. Adjust the capital letters:

Jeden Tag fährt mein Vater mit dem

Auto in die Stadt.

Depending on the level of ability, you may like to colour-highlight the verb to emphasise its position as second idea rather than second word.

Repeat with another one or two sentences, then let students work on their own. Try an oral assessment. Can they, having heard a S V TP sentence, orally repeat the same as TP V S?

The Teacher's Pet text tool by Chris Lacey, can also be used to generate sentence unjumbling exercises (Sentence Jumbles) in Microsoft Word.

Reordering the lines of a text: textsalad

Another type of exercise might involve arranging the jumbled lines of a text, e.g. a set of instructions, into their correct order using drag and drop. An example follows. Such exercises are often called textsalad exercises and feature in suites of authoring programs such as Fun with Texts, in which the teacher enters a text in the correct order and the program jumbles it automatically and converts it into an interactive exercise for the learner: http://www.camsoftpartners.co.uk/fwt.htm

Making a pot of tea

The Teacher's Pet text tool by Chris Lacey, can also be used to generate line unjumbling exercises (List Jumbles) in Microsoft Word.

Make a list of the grammatical points in the language/s you teach that would be best tackled by using the drag-out-drop facility to change the word order of a sentence or to put the jumbled words of a sentence into the correct order. Devise a minimum of instructions for students for at least two sample exercises.

Create a plain text, i.e. no adjectives or adverbs, using familiar language. Restrict the length to about 2/3 of a screen for ease of working. Below the text create a table into which you enter adjectives and adverbs/adverbial phrases.

Students are asked to either copy and paste or cut and paste adjectives and adverbs into the text to make it more interesting. Depending on the language being learnt, reminders about agreements and positions of adjectives should be given.

When the exercise is completed, students read their versions aloud, so as to compare theirs with the other versions.

When I go out at the weekend, I make an effort to look my best. I go out Saturday evenings with friends. I begin my preparations at 4 o'clock, when I have a shower. I wash my hair and dry it with the drier. I then check my face. Good! No spots! I apply deodorant and perfume and lie on my bed relaxing for half an hour. I then dress. I might try three or four outfits before I decide what I am going to wear. The red dress? The blue trousers? With the white shoes? Or the brown boots? Sometimes I decide to wear what I first tried on! It takes at least two hours. I am ready when my friend comes to call at 7 p.m.

| real | long | new |

-

|

usually | slowly |

| genuine | quick | old |

-

|

frequently | as quickly as possible |

| good | protracted | cotton |

-

|

often | roundabout |

| proper | extensive | silk |

-

|

nearly always | carefully |

| very | favourite | leather |

-

|

without fail | fastidiously |

| comfortable | satin | jazzy |

-

|

rapidly | luxuriously |

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

stupidly | rarely |

Why is an exercise like this more efficiently achieved on a computer screen than on a piece of paper?

In a language such as German it is a straightforward task to emphasise the case endings. A text is created with the information words such as nouns and adjectives missing, though the grammatical ending is present: e.g. adjectives missing:

In einem ...en Haus wohnten ein ...er Mann und eine ...e Frau. Das ....e Haus war zu groß für zwei Leute. " Ach wenn wir nur ein ...es Kind hätten," sagte die ....e Frau. "Unmöglich!" antwortete der ....e Mann.

A list of adjectives appears in a table below. Students copy and paste adjectives into the text, removing only the ... and leaving the endings.

| klein | groß | schön | nett | niedlich | hübsch | süß | alt | jung | dick | dünn | häßlich |

It is also possible, of course, to leave in the adjectives and blank out the case endings, which have to be inserted by the learner.

The deletion of the … is asking for trouble! Students unskilled in keyboard control may unintentionally wipe out the endings too. How could you get round this?

Cloze procedure was invented by Wilson Taylor: Taylor W.L. (1953) "Cloze procedure: a new tool for measuring readability", Journalism Quarterly 30: 415-433. Cloze procedure was originally conceived as a tool for measuring the readibility of a text or a learner's reading comprehension level and derives from the gestalt psychology term "closure", whereby people tend to complete a familiar but incomplete pattern by "closing" the gaps. In Cloze tests or exercises every nth word (usually 5th to 7th) or a certain percentage of a text is blanked out and the learner has to fill in the blanks with a suitable word.

In the days before computers the words had to be blanked out by hand, but now the job can be done quickly and efficiently with the help of a word-processor or automatically with the aid of an authoring program: see Module 2.5, Introduction to CALL authoring programs. Cloze procedure, including so-called total Cloze, where the whole text is blanked out, figures in numerous CALL programs: see Section 8.3, Module 1.4, headed Total text reconstruction: total Cloze. Such programs generate the blanked out texts automatically and convert them into interactive exercises for the learner.

There is Cloze-exercise generator

(for printable exercises) at the Goethe-Institut website - which will also generate

other types of exercises:

http://www.goethe.de/lhr/prj/usg/deindex.htm

The Teacher's Pet text tool by Chris Lacey, can be used to generate Cloze exercises in Microsoft Word.

A wide range of matching exercises can be created with a word-processsor. In the following example a table has been created in which the two halves of well-known proverbs have been jumbled up. The lerner's task is to drag the second half of each proverb in the second column to match the first half of each proverb in the first column. Similar exercises can be set up for matching synonyms or antonyms and matching words with pictures.

| All is fair | the harder they fall |

| The bigger they are | according to your cloth |

| Don't make a mountain | in love and war |

| Cut your coat | out of a molehill |

These are the main ways in which so-called "foreign characters", i.e. characters bearing accents or other diacritics, and special characters not normally found in the standard Roman alphabet, can be entered into a word-processor or other software tools for creating texts, e.g. PowerPoint and email programs such as Outlook or Eudora.

If you are using a UK keyboard layout you can

generate accented characters with special dead keys in Microsoft Word.

You first press the dead key that represents the accent or diacritic you wish

to use and then follow it with the character that requires that accent or diacritic.

The dead keys have been chosen to be mnemonic. Note that some dead keys appear

on the shifted key, so the

You can insert foreign characters and special symbols by using the Symbol command on the Insert menu on the Main Menu bar in Microsoft Word. Click on Insert on the Main Menu bar and choose Symbol. Choose the Font, e.g. Arial or Times New Roman. This will cause a chart to pop up showing the foreign characters and other special symbols that are available for that font. Click on the character or symbol you wish to use and then click on the Insert button on the pop-up chart. This will cause the character or symbol to appear at the point in your text where you are currently working. Close the pop-up chart when you have finished inserting special characters and symbols.

You can also assign characters to shortcut keys via the pop-up window that appears when you select Insert / Symbol from the Word Main Menu bar.Click on Insert on the Main Menu bar and choose Symbol. Choose the Font, e.g. Arial or Times New Roman. Click the symbol or character you want on the font chart showing which symbols and characters are available. Click the symbol or character you want. Click Shortcut Key. In the Press new shortcut key box, type the key combination you want to use, e.g. CTRL + a letter. But make sure that you don't overwrite existing shortcuts that are built into Word, e.g. CTRL + F for Edit / Find and CTRL + V for Edit / Paste. Click Assign. In the Save changes in box choose where you want to save the new shortcut, e.g. in the NORMAL.DOT file (which stores general information relating to Word) or the name of the document that you are currently working on. If you are using a computer that is shared with other people in a school or college it is inadvisable to save the new shortcuts to the NORMAL.DOT file as this will affect other people using the computer who type in different languages. Some ICT managers will not allow this in any case and may have blocked this facility

Alternatively, you can load up the Character Map at the beginning of a work session, minimize it and let it sit on the Windows taskbar until you need it. The Character Map is accessed via Programs / Accessories / System Tools / Character Map and will work in most Windows applications - check this with your ICT manager, as he/she may have moved it elsewhere!

The top row of the alphabet on English language keyboards begins with the letters QWERTY - which is why such keyboards are known as QUERTY keyboards. European French keyboards begin with the letters AZERTY, and German keyboards begin with QWERTZ. Windows allows you to change the keyboard layout to that used in a variety of different countries, so that characters with diacritics can be typed more easily, but this may be confusing as the whole keyboard layout changes and you find that symbols such as @ and # are also in a different place. If you wish to try remapping your keyboard you can do this via the Control Panel and Regional and Language Options facility in Windows. To change the keyboard languages and layout in Windows XP, click Start, then choose Settings / Control Panel / Regional and Language Options. Click the Languages tab, then the Details button, the Settings tab, and the Add button. Now choose your required language. Click the OK button to close the input window. If the added language is a permanent choice, click Apply to finish the process For an illustrated version of these instructions see Keyboard Help: Adding International Keyboard.

It's usual for computers in Canadian educational institutions to be set up in this way for English and French, but they use the Canadian French layout (which is one of the options in Windows) rather than the European French layout. The Canadian layout is better if you intend to toggle between the two systems as it offers access to the diacritics using dead keys or other pre-set keys, but it is still a QWERTY keyboard and you don`t have to think about the A, Q, Z & W being in the wrong place.

You can also consider buying a foreign keyboard if you work most of the time in a specific foreign language.

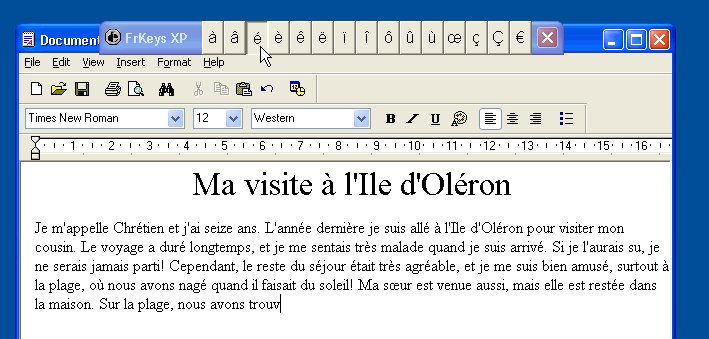

The easiest way to enter foreign characters is to use a foreign characters utility program, such as FrKeys. Using FrKeys you do not need to remember convoluted combinations of keys. FrKeys places a small toolbar containing the foreign character keys at the top of any Windows application (see illustration below). Instead of typing the foreign characters you just click once with the left mouse button and the character appears at the point in your text where you are currently working. Character sets for the commonest European languages are supplied with FrKeys, and you can add extra character sets using a character creation facility within the program. Mathematical symbols can also be inserted in the same way as foreign characters.

Screenshot: FrKeys

A survey conducted in 1998 by David Wilson, and again in 2005 by Graham Davies, through the Linguanet Forum showed that most people still preferred the old-fashioned way of typing foreign characters, i.e. by holding down the left ALT key on the computer keyboard, pressing a sequence of three digits (the ASCII code) or four digits (the ANSI code) on the Number Pad, and then releasing the ALT key. The advantage of this method is that it works in more or less any software application and on computers with non-standard keyboard configurations. The main problem with this method is that you either have to fix the codes in your head or have access to a chart showing the correspondence between the characters and the codes. If you are using a laptop that that does not have a number pad then this method is extremely laborious and you will find it more convenient to use a program such as FrKeys. See the Glossary for explanations of the abbreviations ASCII and ANSI.

Posting charts of commonly used foreign characters in a very large font on the walls of the language centre is a solution adopted by some schools. The following character table contains a selection of commonly used characters and their ASCII codes. A more comprehensive table in Word format - including accented capital letters and digraphs in French - can be downloaded by clicking here: ForChars.doc. The Word table displays both the ASCII and the ANSI codes for each character. See also Keyboard Help: ALT Key Codes & Charts.

Character table: commonly used foreign characters and their ASCII codes

|

FRENCH à 133 |

GERMAN ä 132 |

SPANISH á 160 |

ITALIAN à 133 |

NORDIC å 134 |

Unicode is a character coding system designed to support the interchange, processing, and display of the written texts of the diverse languages of the modern world. Essentially, computers work with numbers and each character that you type on a computer has been assigned a number. Before Unicode was invented, there were hundreds of different encoding systems for assigning these numbers, which was somewhat chaotic, and not all languages were covered. This has changed with the advent of Unicode. Unicode covers all the characters for all the writing systems of the world, modern and ancient. It also includes technical symbols, punctuation, and many other characters used in writing text. Unicode is built into modern versions of Windows and operating systems used by other types of computers, thereby making a wider range of alphabets and syllabic systems available.

It is possible to buy font sets for less common languages. Try the Linguist's Software website, which offers a wide range of fonts for languages from all over the world.

Additional punctuation marks and accented letters are accessible when the iPhone or iPad keyboard is displayed. If you hold your finger down on a letter instead of tapping it you will see a selection of alternative accented letters. Slide your finger along to the one that you want and then raise your finger quickly.

NoTengoEnie: Click on the character you wish to type and then paste it into your document.

Spellcheckers have been included as part of word-processing packagess for some time. A spellchecker is an electronic dictionary that scans the text entered by the user and highlights any word that it does not recognise. The author of the text is then given the option to correct, ignore or add any highlighted word to the dictionary. Spellcheckers can be set to accommodate different varieties of a language, e.g. British or American English, and many other languages.

You may also find that your word-processor includes a grammar checker, a style checker and a thesaurus (see Section 6.2, below). All these tools have to have to be treated with considerable caution, as they are designed to be used by native speakers and they therefore assume a reasonable level of competence in the target language. The suggestions that they offer may not be understood by a non-native speaker, and may not be good advice anyway.

There are two useful articles that discuss in detail the effectiveness of grammar checkers and style checkers. The first describes an experiment with students of English as a Foreign Language conducted by Yu Hong Wei at Thames Valley University. This article is available on the Web: "Do grammar checkers work?" (Yu Hong Wei & Davies 1997). The second describes an experiment conducted by Jacobs & Rodgers (1999) with university level students of French. Both articles come to similar conclusions: that grammar checkers do have some value for learners of foreign languages but students must be made aware of their shortcomings and to treat every piece of advice with caution - hence the title of the article by Jacobs and Rodgers: "Treacherous allies". See also Tschichold (1999).

Spelling and Grammar Checkers by Ultralingua

Ultralingua's Spelling and Grammar Checkers offer a range of useful spell-checking and grammar-checking facilities for English, French, Spanish and German, including:

As well as offering online and offline dictionaries, Ultralingua offers a the WebLex facility that can convert a Web page into a "dictionary-enabled" page, so that the words on the page are clickable and can be looked up in a defining dictionary (English) or a bilingual dictionary. You type or paste the URL of the Web page into address box and choose the source and target language. The original Web page is then made available as a dictionary-enabled, clickable page. Some Web pages can't be dictionary-enabled, but it works most of the time. Includes verb conjugation tables too.

VoyCabulary

VoyCabulary makes the words on any Web page into links so you can look them up in a dictionary or other word-reference-site of your choice, by simply clicking on the words. Anytime you find yourself reading a Web page with words you wish to look-up, try running the page through VoyCabulary and just click on the words.

A variety of activities can be created by using an electronic thesaurus that forms part of a word-processing package, e.g. in Microsoft Word. Take a look at the following text, which is an extract from Davies (1996):

It is not uncommon for training to be given a low precedence. This is true both of the business and of the education sector. There is a customary myth that once someone has been on a training course they need never go on another one. We all know this is gibberish, but unfortunately this cuts little ice with the accountants, who are only too aware that the training budget is one of the easiest to cut. There is also a youthful belief that sending a language teacher on a general training course in the use of computers is ample. This is also baloney. Training must be an incomplete process, and language teachers need properly tailored courses.

Here we can learn a lot from the past. Lack of training sounded the death-knell of the language lab. I belong to the cohort that was trained in the early 1960s, when the reel-to-reel tape recorder and the film strip projector were the main technological aids that the language teacher used - if at all - and the language lab was the most modern form of technology the new generation might expect to use - which we got quite eager about. The 1960s and 1970s saw a rapid growth in language labs, boosted by the then chic audiolingual approach to language teaching, followed by a rapid deterioration. Why the growth and why the deterioration?

The original text has been modified by clicking on selected words, calling up Word's thesaurus (Shift + F7) and replacing each of the selected words with one of the thesaurus's suggested synonyms. As any experienced writer knows, a thesaurus has to be used with caution: context is crucial, and a thesaurus is best used when combined with a dictionary and a concordancer: see Module 2.4, Using concordance programs in the Modern Foreign Languages classroom. A useful exercise for the advanced learner is to attempt to spot which words in the text have been replaced with synonyms and which synonyms are unacceptable. Using Word's thesaurus, the learner can then attempt to find more acceptable synonyms and get back to the original text - or as close to it as possible.

Claire Bradin: University of Pittsburgh, USA: Word-processing-based activities for a language class

MFL Sunderland: Lots of useful downloadable resources and information here and links to other useful sites. Created and maintained by Clare Seccombe.

MFL Resources: This website contains a number of downloadable resources created with Microsoft Word.

Teacher's Pet: A website created by Chris Lacey. This site offers a free text tool, a Microsoft Word template which contains sets of macros that can make simple but very useful changes to texts in order to create word-processing exercises, e.g. removing spaces, removing vowels, word-jumbling, sentence jumbling, breaking sentences in half, etc. See the Using Teacher's Pet tutorial by Joe Dale at the CILT website.

Vance Stevens: Language learning techniques implemented through word-processing: grammar-based exercise templates for becoming proficient with word-processing. Available at: http://www.vancestevens.com/wordproc.htm

Hardisty & Windeatt (1989): An old printed publication, but the ideas are still good.

PowerPoint is a popular presentation software application and is widely used by language teachers. Presentation software was designed originally with business and academic presentations in mind as an alternative to the overhead projector, for example to present lists of keywords and bullet points to accompany a promotional presentation or a lecture. Modern versions of PowerPoint can do much more than this. In the modern languages classroom, PowerPoint can be used effectively to present a variety of aspects of a new language, e.g. dialogues, grammar, vocabulary, and as a stimulus for group exercises and activities, with enhancements such as animated text on screen, pictures and audio and.video clips. See Section 8 (below) and this tutorial on Embedding YouTube Video into PowerPoint 2007.

Learning how to use PowerPoint is not very difficult. The skills you need are very similar to those needed for word-processing: see Section 1.2. Materials that you have already created with a word-processor can be copied and pasted into PowerPoint. If you are new to PowerPoint have a look at the PowerPoint Tutorials at the Internet4Classrooms website. See our "can do" list for PowerPoint to check your progress: ICT_Can_Do_Lists.

If you are putting together a new PowerPoint presentation, start with Word. Using the Outline facility in Word (which is accessible view the View menu) type all your main headings and subheadings and then send them to PowerPoint. The Outline facility will help you get the content and structure right, and then you can add in all the glitzy presentation features afterwards. The Internet4Classrooms tutorial explains how to do it: Sending a Word Outline to PowerPoint.

Bear in mind that there is a danger of over-using or misusing PowerPoint. Use Google to search the Web for the phase "Death by PowerPoint" and you will find numerous references to PowerPoint presentations that are as exciting as counting sheep. Too many lessons delivered with PowerPoint are one-way presentations that lack interaction and look more like a corporate board meeting, complete with endless slides full of bullet points. "Click and talk" has replaced "chalk and talk".

See this amusing video on YouTube by Don McMillan, which illustrates some common mistakes in PowerPoint presentations: Life After Death by PowerPoint

PowerPoint can be particularly effective when used for whole-class teaching, especially with an interactive whiteboard (IWB). See: Section 4, Module 1.4, headed Whole-class teaching and interactive whiteboards, where you will find a list of resources suitable for use on an interactive whiteboard or a computer linked to a standard projection screen.

Two more ideas:

Graham Davies writes:

It should be emphasised that it is more important to develop good presentation techniques for whole-class teaching with a computer rather than using techno-gimmicks. Besides PowerPoint, there are many software packages that can be used in both one-to-one mode and in whole-class teaching. For example, multimedia simulations such as Who is Oscar Lake? ( Section 3.4.9, Module 2.2). and text manipulation packages such as Fun with Texts (Section 8, Module 1.4) lend themselves to exploitation for whole-class teaching.

Adding pictures and sound to Word and PowerPoint documents can make them much more attractive. Sound, in particular, is a useful addition to a Word document or a PowerPoint presentation used in language teaching.

First, you have to collect together your pictures and sound clips. Pictures can be gathered from a variety of sources, e.g. from the Web, from a CD-ROM, or from your own collection of photographs. There are a number of clipart libraries on the Web. See Graham Davies's Favourite Websites page under the heading Clipart and image libraries.

CD-ROMs containing copyright-free images can also be bought at a modest cost in most PC stores. But scanning in your own pictures, using a flatbed scanner, is a lot more fun: see Section 1.3.3, Module 1.2. The pictures can then be edited with a picture editing package such as LView Pro or Corel's Paintshop Pro.

Audio clips can also be found on the Web: see Graham Davies's Favourite Websites page under the heading Audio Clips.

You can also make and edit your own audio recordings. This is not the daunting task that most language teachers imagine it to be. Most PCs come equipped with the necessary software to do it, e.g. Windows Sound Recorder, which is usually found in the Windows Accessories folder on your computer. A better (free) package for making and editing sound recordings is Audacity: see Section 2.2.3.3, Module 2.2, headed Sound recording and editing software.

Note that there may be copyright restrictions on images and sound clips that you find on the Web. See our General guidelines on copyright.

It is assumed that you know the basics of creating a Microsoft Word document. The following procedure is common to most recent versions of Microsoft Word.

Start a new document and type in some text.

First, insert a picture into the document:

On the Main Menu bar, click on Insert

A sound clip icon will appear and it can now be positioned in the Word document

Save the document in the usual way – but remember it will be quite large now as it contains a picture and a sound file. Re-open the document, and you will find that the picture appears automatically. Double-clicking on the sound clip icon will cause the sound file to be played.

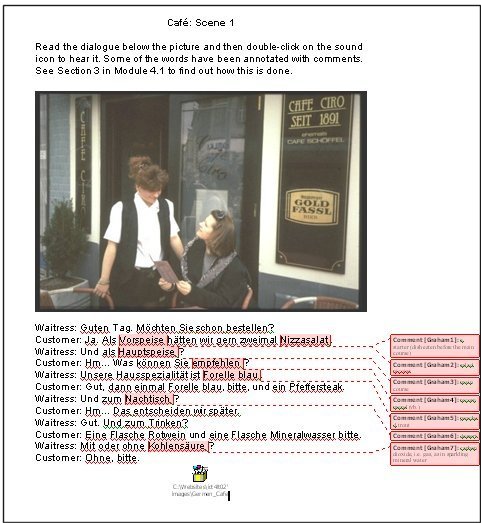

A demonstration downloadable Word document containing a picture, the text of a dialogue (with selected annotated words) and a sound file can be downloaded by clicking here: Cafe.doc

If you are wondering how we created the comment notes relating to the vocab in this document, see Section 3, Module 4.1, headed Using a word-processor for marking and giving feedback. This describes how it is done and how to use comment notes in correcting students' work that has been submitted in Word format.

Screenshot: Electronic Worksheet

Word offers considerable possibilities for producing handouts and electronic worksheets along the lines of the above document. The text, sound file and picture in the above document are both taken from the TELL Consortium German Encounters CD-ROM.

Enhancing a PowerPoint presentation with pictures and sound is also fairly straightforward. The method is similar to that described for Microsoft Word (Section 8.1, above). It is assumed that you know the basics of creating a PowerPoint document. The following procedure is common to most recent versions of PowerPoint.

Start a new PowerPoint presentation and create a single slide. Type in some text.

First, insert a picture onto the slide:

The picture will appear on the slide and it can now positioned anywhere on the slide

Now insert a sound file onto the slide:

A speaker icon will appear and it can now be positioned anywhere on the slide.

Save the document in the usual way. Re-open the document and run the slide show. You will find that the picture appears automatically. Clicking on the speaker icon will cause the sound file to be played.

This is how you break up the long Welsh place name in Section 3.1:

Llan-fair-pwll-gwyn-gyll-go-ger-y-chwyrn-drobwll-llan-tysiliog-ogo-goch

meaning...

The church of St Mary, in the valley of the white hazel (trees), near the rapid whirlpool, near the red cave of the church of St Tysilio

llan = church or (here) Saint

fair = Mary (mutation of Mair: Saint's name)

pwll = valley, hollow

gwyn = white

gyll = hazel (mutation of cyll)

go = about, (almost) at

ger = nearby

y = the (often omitted)

chwyrn = rapid

drobwll = whirlpool (mutation of trobwll)

llan = church or (here) Saint

tysilio(g) = of Tysilio (Saint's name)

ogof = cave (f is dropped at the end)

goch = red (mutation of coch)

Note: Mutations of the initial letters occur in all Celtic languages, subject to a set of rules which are too lengthy to explain here.

Crystal D. (1987) Encyclopedia of Language, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davies G. (1997) "Lessons from the past, lessons for the future: 20 years of CALL". In Korsvold A-K. & Rüschoff B. (eds.) New technologies in language learning and teaching, Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Also on the Web in a revised edition (2009) at: http://www.camsoftpartners.co.uk/coegdd1.htm

Gray C., Hagger-Vaughan L, Pilkington R. & Tomkins S-A. (2005) "The pros and cons of interactive whiteboards in relation to the Key Stage 3 Strategy and Framework", Language Learning Journal (ALL) 32: 38-44..

Hardisty D. & Windeatt S. (1989) CALL, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jacobs G. & Rodgers C. (1999) "Treacherous allies: foreign language grammar checkers", CALICO Journal 16, 4: 509-530.

Rendall H. (2003) "Developing neural pathways: making the most of computers", Scottish Languages Review 8, June 2003, Scottish CILT.

Rendall H. (2006) Patterns and procedures: focus on phonics and grammar, London: CILT.

Stevens V. (2003) Language learning techniques implemented through word-processing: grammar-based exercise templates for becoming proficient with word-processing. Available at: http://www.vancestevens.com/wordproc.htm

Tschichold C. (1999) "Intelligent grammar checking for CALL". In Schulze M., Hamel M-J. & Thompson (eds.) Language Processing in CALL, ReCALL Special Issue: 5-11

Walker R. (2003) "Interactive whiteboards in the Modern Foreign Languages classroom", TELL&CALL 3, 3: 14-16.

Yu Hong Wei & Davies G. (1997) "Do grammar checkers work?" In Kohn J., Rüschoff B. & Wolff D. (eds.) New horizons in CALL: proceedings of EUROCALL 96, Szombathely, Hungary: Dániel Berzsenyi College. Also on the Web at: http://www.camsoftpartners.co.uk/euro96b.htm

If you wish to send us feedback on any aspect of the ICT4LT website, use our online Feedback Form or visit the ICT4LT blog.

The Feedback Form and a link to the ICT4LT blog can be found at the bottom of every page at the ICT4LT site.

Document last updated 14 June 2012. This page is maintained by Graham Davies.

Please

cite this Web page as:

Rendall H. & Davies G. (2012) Using

word-processing and presentation software in the Modern Foreign Languages classroom.

Module 1.3 in Davies G. (ed.) Information and Communications Technology for

Language Teachers (ICT4LT), Slough, Thames Valley University [Online]. Available

at: http://www.ict4lt.org/en/en_mod1-3.htm

[Accessed DD Month YYYY].

© Sarah Davies in association with MDM creative. This work is licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.